Florah Kwinda

Florah Kwinda

I was born in this same area where I am still living now. Long, long ago. Sometimes, when we sit talking at night around the cooking fire in our kitchen hut, my friends say it was better in the olden days. In those days we had more rain, the mealies (corn) grew taller, we had more goats and hens and eggs, but I do not think it is true. I can remember years of drought. Yes, there was rain but I can also remember poverty and hunger and drought. My many sisters and brothers and I did not go to school, there were no schools in this area, much later there came a school and I learnt to write a little. At that time we did not have schools or shops or roads. Later, when I was a teenager a white farmer bought a farm close to where we were staying. He started cutting away the bush and employed my whole family and other families too. He said he wanted to plant tomatoes.

“What is that?” we asked ourselves. We only knew miroho, wild spinach.

The farmer and his wife realised we had no food at our homes; we were hungry in the mornings and could not work so well. From then on, early in the mornings one woman had to make a fire and cook a huge pot of porridge for all the workers.

“You must come to work before sunrise,” the man said, “and eat first.”

He did not have to ask us to come to work earlier, we could not wait to get to work. Before we fell asleep we were thinking of that big pot of steaming porridge. We dreamt of that big pot of steaming porridge.

Soon we knew what tomatoes were and learnt how to cook them with our miroho. We learnt how to sort tomatoes for the market, and the rest that were not good enough to pack into boxes we could take home, the farmer said. Our life changed. We had enough to eat.

After some time the farmer told us it was the end of the first month.

“What is that?” we wondered. We stood in a line and received money. Many of us hadn’t seen paper money before, the coins we knew, but what were we to do with the paper?

The farmer’s wife, who could also speak Tshivenda, explained to us that paper was of more value than the coins. We laughed and shook our heads. How could that piece of paper be more than shiny shillings?

“I’ll take you to Musina, to the shop,” she said.

One afternoon she took us all in the big truck to Musina. In those days there was one shop in Musina.

“Come!” she said, but we did not want to get down from the truck. My mother sent me and my sister to follow the farmer’s wife into the shop. The whole shop was full of wonderful things, mealiemeal in bags as high as the roof, bags and bags of sugar, a mountain of yellow pumpkins, bags of salt, a whole row of bicycles, a crate full of white shoes. As our eyes got used to the dim light inside we saw more and more wonderful things: loaves and loaves of bread, eggs in big wooden boxes, bottles of Vaseline, bars of blue soap, candles, small bags of tobacco all stacked up, blue dresses and red dresses that could fit me and my sisters and my mother. We turned around and walked out.

“Don’t you want to buy anything?”

We were confused. We climbed back onto the truck. Other people bought packets of sugar and tea or coffee, but we were all so confused. One man bought a pipe and a bag of tobacco.

Back on the farm the farmer’s wife handed a parcel to every family: enough sugar, and salt and cornmeal for one month.

We thought this life would never end, but years later the farmer and his wife moved away to Louis Trichardt. We could no longer stay on that farm. My children and I moved to this side of the mountain. My husband could not find work and again I knew what poverty was. One day Selinah Mavhetha called me over and showed me how to hold a needle and how to embroider. In the beginning I did not do well, but after many embroideries that were too tight – we call it kokhodza – I understood what to do and how to do it.

I am now an old woman but another wonderful thing happened to me. Selinah came to me one morning. She said, “Ina phoned, she wants to know if you are willing to go to Johannesburg and learn a new design?”

“I have never even been to Louis Trichardt or Polokwane and now Johanneburg!” I said.

“I’ll send my son Peter with you to Sibasa and there he will put you on the bus,” Selinah said.

Peter came with me on the first part of the journey to Sibasa and lent me his cell phone. At Sibasa he bought my bus ticket and showed me the cell phone. “You press this button, then Ina will speak and then you tell her when you are close to Johannesburg,” Peter said.

“But how will I know when I am close to Johannesburg?” I asked.

“Eish!” Peter said. He found an old man with an honest face who was also getting onto the bus and said, “Will you please help this woman. Press this button on the cell phone and tell them on the other side as soon as you get close to Park Station in Johannesburg.”

I traveled all day on that bus.

In the afternoon the old man pressed the button and said, “We are close to Johannesburg.” Before he killed the cell phone I asked to say something too.

He gave me the phone. I said, “I am wearing a white head cloth and a red nwenda – a nwenda is our traditional Venda dress – don’t loose me.”

When I arrived at Park Station Ina was waiting for me. I spent a whole week in Johannesburg learning the new design. For me it was like a holiday. I did not have to walk a long way every morning to fetch water and firewood. There was water in the taps. When I got home after that week I asked Peter to phone Ina and tell her that if she has a new design again she must please phone me, I’ll come.

Ina’s side of the story

I sat with my interpretor, Johannes Mavhetha, on a low mud wall next to a diminutive woman surrounded by a crowd of children aged from 2 to 20 years. Florah Kwinda was one of the best embroiderers in the Tambani project. At quilt shows, Florah’s work sold first. “‘This is very high quality work!’ ‘Is this done by machine? No? All by hand?’ Yes, all the handwork of a Venda woman with many granchildren living in a clay hut she built with her own hands.

‘Florah, here are so many children you have to care for, your own grown-up children and then all these grandchildren. Your house must be full?’

‘Yes, my house is full, we don’t have enough space. Me and my husband built this house with our own hands. First we made the bricks and left them to dry in the sun. After that we started building.’

‘Tell me Florah, what makes you happy?’

Flora sat quietly for a long time before answering, ‘When I have enough food for my children, that makes me happy.’

‘What can I do to help you, Florah?’

‘Send me more cloth and yarn to embroider. This is my only way to earn money. I am not a very strong woman but now I can sit here in my own kitchen and embroider. Yes, more cloth, please.

‘I am also happy to see my washing on the line. For us washing is not one-two-three. That is why it is wonderful to see your washing on the line. We do not have running water in our village. Our nearest water tap is down this road and there at the second corner you turn left. Walk a short way on that road and then you come to the tap. So it is a wonderful thing to see my washing on the line.’

‘What is the most important thing in your house? I’m not talking of your children and your husband, they are important to you, I know, but what is the best thing in your house?’

She leads me into the dark and cool interior of the little house. ‘The first thing I bought for my house after I joined the embroidery group was this wardrobe. Everything is so untidy when you do not have a proper cupboard or box in which to pack clothes. But before I bought this wardrobe we had to build a four corner room. You know that we Venda people live in round huts. We know well how to build a round hut and thatch the roof. The building of such a hut is very important and we all know how to do it, but a wardrobe does not stand easy in a round hut. A wardrobe likes to have a flat wall behind him to lean on. My husband and I built this room, it has four corners. Then we bought this wardrobe.’

‘The second very important thing in my house, something that brought happiness to me and my husband and my children is this television. It is

not a new one but most of the time it works. The room is small but it is big enough for our family of ten and also the children of Rosina Mukwevho who lives behind us. There is much laughter and happiness when we watch the lives of other people in the stories on television. We forget our own troubles. (This is much the same as with their folktales – see Interpretations at the end of each story. Ed.)

‘The first thing I do with the embroidery money is buy a 8Okg sack of mealiemeal (corn meal) for a month. We are ten mouths. Sometimes in a good month I buy tomatoes, potatoes and onions to eat with the mealiepap. This is the money that comes from the embroidery. I use it for vegetables. Near the end of each month I look at the sack of mealiemeal. I see the food is getting less and less. I make a plan, I use less. I tell the children, ‘From today we are going to eat soft porridge!’ Every day I thin the porridge down so it can last longer. ‘

‘Near the end of the month the sack of mealie meal is nearly finished and we eat very thin porridge. And then one morning Selinah (Mavhetha, the supervisor of the Folovhodwe embroidery group) calls out in a loud voice, ‘Ina phoned from Johannesburg, she wants the embroideries.’

‘Selinah walks down the road to go and tell Heleni Mukwevho and Tshumbedso and Melodi and Vidah Kwinda and all the other embroiderers to hurry up and bring everything to her house. We all rush to finish the last stitches. I find a piece of paper and write my name, “Florah Kwinda”. I sew the piece of paper with a few long stitches through all my finished embroideries. Tomorrow Mashudu will come from Muswodi to collect all the embroideries from Folovhodwe. The next day she will leave at four o’ clock in the morning to catch the bus in Sibasa that will take her to Johannesburg.

Then we wait for Mashudu to return with money in plastic bags. Sometimes the embroidery money arrives just in time. There is no food left. The mealiemeal bag is empty.

Late one afternoon we hear Mashudu greeting Selinah in a loud voice:

“Aa Vho- Selina” (Good day Mrs Selina)

“Aa ndimadekwana Mashudu!” (Good evening Mashudu) We rush over to Selinah’s home. The embroidery money has arrived just in time. Selinah reads the names written on the small plastic bags. “Rosiena Mukhwevho!”

“Yes here am I!” Rosiena takes the money with both hands, goes down on one knee and says, “Rolivhuha” – Thank you. That is the way we Venda people show respect when we receive something.

“Vidah Kwinda!” “Yes here I am!” “Melodi Nefolovhodwe!”

One by one the names of the embroiderers are called out, my name too. The embroidery money arrived just in time.

We walk over to the Indian shop. The shop is still open, there is a paraffin lamp on the table where you pay. Mr Chatna the shop keeper looks tired and wants to close the door for the day. His mother sits in a wicker chair behind the counter already fast asleep. I buy two loaves of white bread, a small tin of mixed fruit jam and a box of tea. It is very dark outside but my feet know the way. Tonight we will have a feast.

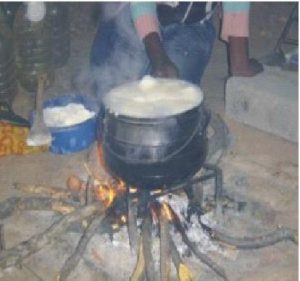

‘Here is my kitchen. Every morning I clean out the ash and wash the pot before I settle down with my embroideries.’

A Venda kitchen is not only a place to cook the meals, to eat and sit around the fire in the evenings listening to folktales. A

Venda kitchen also has room for hens sitting on eggs. It is a safe place for a hen. Here nobody bothers her. Children walk carefully around her. This is her corner in the kitchen hut where she can do the thing she likes best and that is to wait for

her chickens to hatch.”

Florah gets a Garden

During one of my visits to Venda I sat with Florah and showed her how beautiful her embroidery looked when incorporated into a wall hanging. At first she didn’t believe it was her embroidery. Then she saw he signature, her name embroidered in the corner.

‘What else can I do for you, Florah?’ Very quietly she said, ‘I cannot embroider any faster.’ I knew that she meant that the money she got for her work was not really enough to care for the whole family and yet she was embroidering as fast as she could. Her husband, Ben, said, ‘She is the only bread winner.’ And hers is a large family, including grown children and grandchildren, ten in all. “My son Sedzani is 20 years old and my second child Tivhadini is 17, they are now trying to get work in Thohoyandou. My third son Mbulaheni is 14 and in high school. My daughters are Murendeni, Rhefilwe, Tikhatali and Ndifelani. Then I have a grand daughter Ndiene. As you see there are many mouths to feed.”

‘Would a garden help? If you could grow some vegetables, but how are you going to water your garden?”

“I’ll carry water in buckets,” Ben said. “I’ll borrow a wheelbarrow to bring water in a big drum. The tap in our street is not too far.”

But there is another problem. As soon as a vegetable garden is planted the goats eat everything. One needs a fence round a vegetable garden and a fence needs strong posts and diamond wire. These are all way beyond their reach. But I had a suprise for them. I had, in my bag, money from a kind donor to pay for a fence for someone in Folovhodwe. Florah came with me to the Indian shop 2 kms away. Yes, Mr Chatna the Indian shopkeeper said, he had a roll of diamond mesh and yes, he would deliver it. Where to? Florah said she would drive with him. In ten minutes he was at her house with the mesh.

A little later I got there and asked where was Ben? “He took the chopper to get 9 poles for the fence.” My heart sank because I hate the chopping down of trees, but . . . Florah and Ben could start a vegetable garden. And Ben? Ben has a new purpose in life.

In August 2011 I visited Florah and her husband again. Where previously there was nothing there was now a garden growing. Embroidering was not the only income and Ben, yes Ben, was a valuable breadwinner growing vegetables.

Shortly before I moved to Napier I received a letter from Florah. It was in Tshivenda: “The money that I received from the embroideries has helped me a lot. I bought mealiemeal and paid school fees. Now I am sick but I could go to the doctor. The embroideries helped me a lot. I pray to God to get better so that I can embroider again. The money from the embroideries really helped me a lot. Florah Kwinda.”

I visited Venda shortly after I received her letter.

“Florah I see in this letter that you wrote to me last month that you are not well. What did the doctor say?”

“I went to Donald Fraser hospital and there the doctor said my heart is not well, it is speaking softly. He listened again to my heart and said he would give me other tablets. He also said I must not do heavy work outside in the hot sun. I told the Venda nurse to tell the doctor that I just work for Tambani doing embroideries in my house and the doctor said that was better than working outside in the hot Venda sun. That is why I am so happy for the embroideries and wrote you the letter. But the doctor at Donald Fraser hospital comes from Cuba and there in Cuba they do not even have a soccer team. You know in the olden days when there was a white government here in South Africa all the doctors in Donald Fraser hospital were missionaries. They came from Germany and Holland and other countries. We called the doctors from Germany the ja! ja! doctors. When you see a doctor from Germany he would ask: “How can I help you, ja?” Then you say, “It is my back, I have a sore back.” Then he said, “Go to the X-ray office down the passage, ja? Then you come back with the X-rays, ja?

“We called the doctors from Germany the ‘jaja’ doctors. These doctors worked so fast and Germany had a very good soccer team. In the one doctor’s office there was a photograph of their soccer team. “Here is the striker,” he once said to my son who went with me to the doctor. My son was very happy to see the striker of the German soccer team. There were also doctors from Holland. Those doctors were so white! Their skin was white, and the hair was white, even the hair around their eyes was white. They also have a very good soccer team but not as good as the team from Germany, my son said. We love to watch soccer. In Absa bank in Musina they put a television high up on the wall so the people waiting in the line can watch soccer. We don’t mind waiting in that line, because we can see soccer. My son said those soccer games on the television in the bank are very old games but we do not mind. Sometimes the bank is full of people just watching soccer. One day it was so hot with all the people that one young man fainted. All those white doctors have left. Now the new government brings in many doctors from Cuba and Nigeria and Ghana.”

Florah died soon after my last visit to her. Sadly Ben was not able to keep the vegetable garden going and sold the fencing to feed the family.